FUNCTIONS AND GENERATORS

by Kirby Urner

First posted: Dec 31, 2005

Last modified: Jan 18, 2006

SOME BACKGROUND ABOUT SEQUENCES

Exhibit 1: Triangular Numbers as Ball Packings

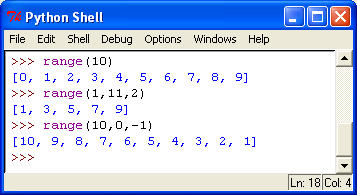

We've

seen how the built-in range function will give you a list of consecutive

integers. You get to define the starting and stopping numbers, where the

stopping number is one step beyond the last integer in the returned sequence.

We've

seen how the built-in range function will give you a list of consecutive

integers. You get to define the starting and stopping numbers, where the

stopping number is one step beyond the last integer in the returned sequence.

You also may define the stepping number: how far to jump each time, up to but not including the stopping number.

Triangular numbers are the partial sums: 1, 1+2, 1+2+3, 1+2+3+4... and so on. How might you use the range function, combined with the sum function, to define a triangular number function? In other words, you'd like tri(1) to return 1, tri(2) to return 3 and so on.

Answer: def tri(n): return sum(range(1,n+1))

However, the young Gauss (on his way to becoming a famous mathematician) showed there's a better way. Imagine the same sequence of consecutive numbers up to N written underneath, but in reverse, and then summing vertically.

1 2 3 4 5 ... 100 100 99 98 97 96 ... 1 ------------------------------- 101 101 101 101 101 ... 101

The answer is the same in each of the N columns: N+1. You'll get twice the answer you're looking for (you used two rows instead of one), so divide by two when you're done multiplying. In other words N*(N+1)/2, gives the Nth triangular number.

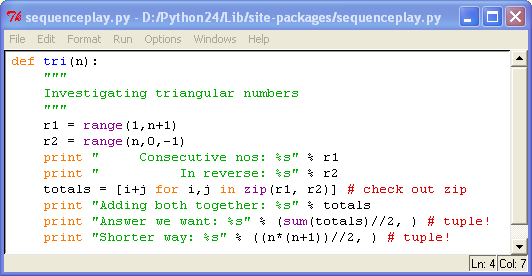

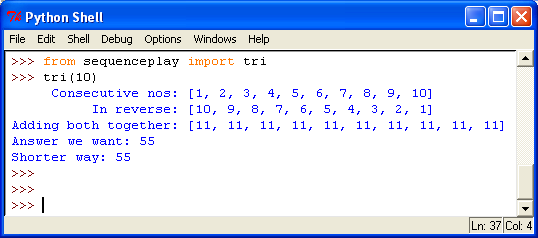

Let's investigate this using Python:

Exhibit 2: Saved module with function, imported and used in the Python shell

How about the

partial sums of triangular numbers, what do they give you? The tetrahedral

numbers! The figure at right shows how triangular numbers, visualized

as ball packings, stack up in layers. Imagine the base growing larger

as the tetrahedron grows taller. The sequence is: 1, 4, 10, 20... We'd

like a Python function to return the Nth tetrahedral number. We could

use the already-defined tri

to help out, even though there's a shorter way.

How about the

partial sums of triangular numbers, what do they give you? The tetrahedral

numbers! The figure at right shows how triangular numbers, visualized

as ball packings, stack up in layers. Imagine the base growing larger

as the tetrahedron grows taller. The sequence is: 1, 4, 10, 20... We'd

like a Python function to return the Nth tetrahedral number. We could

use the already-defined tri

to help out, even though there's a shorter way.

Another sequence based on a growing ball packing is the cuboctahedral sequence. In the figure below, you'll see balls arranged in consecutive shells, starting with a nuclear ball.

Exhibit 3: Tetrahedral and Cuboctahedral Number Sequences

The first shell around the nuclear ball contains 12 balls, then 42, then 92, then 162. Then there's the cummulative number of balls to think about. We'll need two more Python functions for these.

The cuboctahedral sequence is the same as the icosahedral sequence. This is because a cuboctahedral shell may be twisted into an icosahedral shell in a way that keeps the ball count the same (see figure below).

Exhibit 4: Alternative views of the Jitterbug Transformation

The icosahedron is important in nature. It's very strong. The icosahedron is also used in architecture to create geodesic spheres and domes. The New Years ball at Times Square, New York, is a geodesic sphere.

The icosahedron is also the basis for this world map, called the Fuller Projection:

Exhibit 5: Flat earth projection: One Island in One Ocean

FUNCTIONS AND GENERATORS

Functions eat none or more arguments, and return nothing or some object (which object may be a collection). Input arguments may be other functions, because "everything is an object" in Python, and function arguments are just generic arguments.

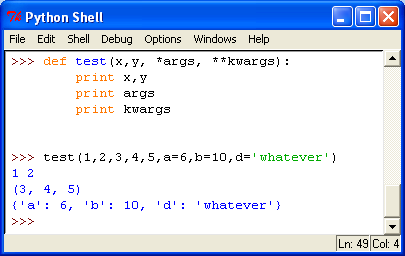

Exhibit 6: special syntax for capturing args, as variables, a *tuple, and/or a **dictionary

You will learn how to predefine inputs with default values,

right in the argument syntax. For example,

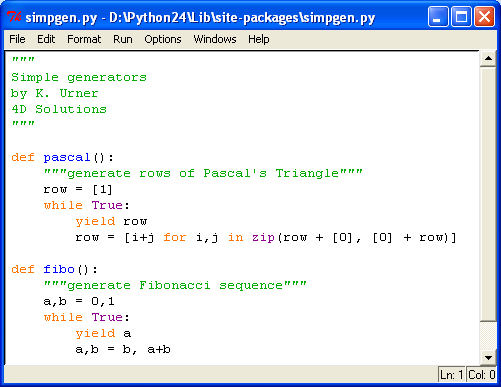

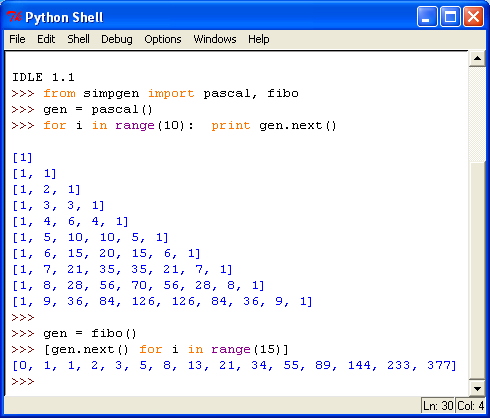

Generators are similar to functions except they retain data between executions, and pick up where they left off, at a yield statement -- similar to a print statement in concept (in Python 2.4, yield doesn't yet accept inputs). Classic examples of generators might include: a generator to produce Fibonacci Numbers; a generator to produce successive rows of Pascal's Triangle (in which both the triangular and tetrahedral sequences appear -- and the Fibonacci).